Rethinking the Safety Triangle: From Heinrich and Bird to a New Era

“The Bird Triangle was wrong, but it changed safety forever.”

For nearly a century, the Heinrich/Bird Safety Triangle has been one of the most recognizable – and controversial – images in safety. It has been called outdated, invalid, misleading, and even dangerous. And yet, few models in our field have had such lasting influence. For decades, it provided managers and supervisors with a simple, powerful way to think about accidents, incidents, and prevention.

Today, however, the very strengths that made the Bird Triangle so effective are also what make it so problematic. Its simplicity created clarity, but also delusion. Its ratios created a sense of predictability, but also encouraged the misallocation of resources. Its popularity mobilized leaders, but often around the wrong priorities.

As we look ahead, the question is not simply whether the Bird Triangle was right or wrong – it wasn’t – but whether we can design a new image, equally powerful, that can mobilize organizations toward real risk reduction and cultural transformation.

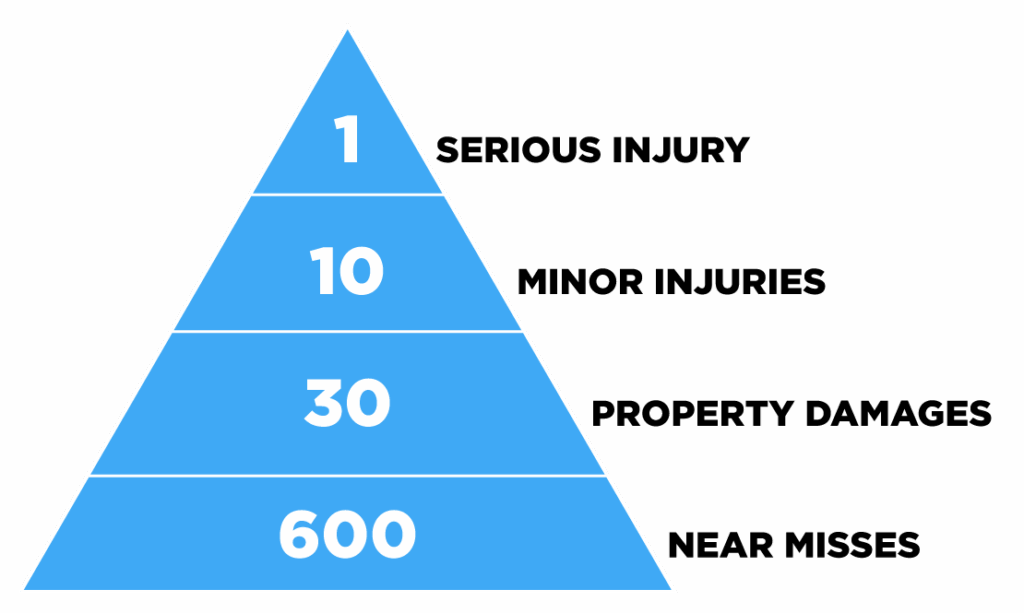

The Bird Triangle: Wrong, but Useful

Bird’s ratios – often expressed as 1 serious injury : 10 minor injuries : 30 property damages : 600 near misses – suggested a predictable relationship between low-consequence events and catastrophic outcomes.

The appeal was obvious. Leaders believed they had found a way to “count their way” to safety by managing minor incidents as a proxy for serious ones. Safety managers finally had an image that created urgency and action from the boardroom to the frontline.

And it worked – at least in the sense of mobilization. The Bird Triangle focused attention on safety like few other tools ever had. It was widely taught, endlessly reproduced, and deeply embedded in corporate safety programs.

But its underlying assumptions were flawed. The ratios were never statistically valid. Preventing sprains and cuts did not prevent fatalities. Companies obsessed over counting injuries, while systemic risks went unnoticed.

The Bird Triangle gave us clarity, but also delusion.

Why We Still Need a Triangle

Despite its flaws, Bird’s Triangle gave us something that modern safety practice often lacks: a unifying image. It was simple, memorable, and easy to communicate. It told a story – albeit the wrong story – that everyone could grasp.

Today, in its absence, safety has fragmented into a clutter of models, tools, and acronyms: energy wheels, sticky notes, safety slogans, and checklists. Each may be useful in its own right, but none has achieved the iconic status or mobilizing power of Bird’s Triangle.

That’s why the challenge is clear: if Bird’s Triangle mobilized leaders – despite its flaws – what image today can unite us and drive action?

A New Triangle for a New Era

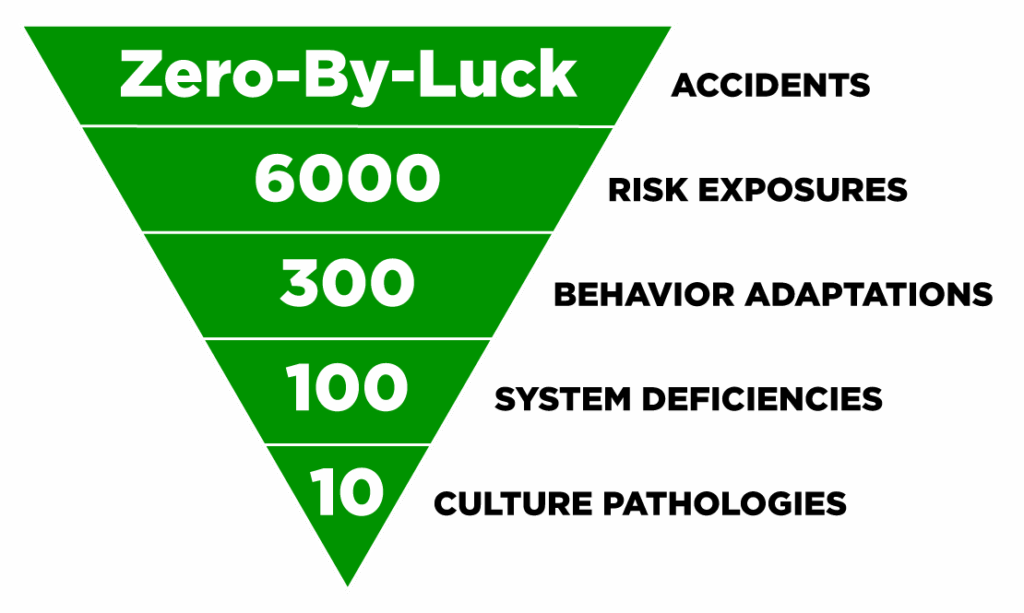

Here is one proposal: Let’s flip the Bird Triangle around, and create a “new a triangle for a new era” that does not count ‘events’, but instead maps the forces that create them and is aligned with modern thinking in safety.

The ratios have not been statistically validated, but may well be close to valid!

The New Triangle: 10–100–300–6000–Zero (by Luck!)

- 10 Cultural Pathologies

At the base are the cultural flaws that undermine safety: rigidity, fear, disconnected leadership, silos, chaos, immaturity, opacity, secrecy, pretension, and delusion. - 100 System Deficiencies

From cultural weaknesses flow cracks in the system: gaps in controls, misaligned incentives, inadequate processes, and fragile defenses. These deficiencies multiply quietly, unnoticed until stress exposes them. - 300 Behavioral Adaptations

As systems fail, people adapt. Workers take shortcuts, supervisors normalize deviance, managers rationalize risks. These adaptations are coping strategies, not recklessness. - 6000 Risk Exposures

Out of these adaptations emerge thousands of risk exposures – moments of vulnerability where failure could occur. Each one is invisible until it aligns with others to produce an accident. - Zero Accidents (Illusion or Achievement?)

And here lies the paradox: even with cultural pathologies, system deficiencies, behavior adaptations, and risk exposures, organizations may still record “zero accidents.” But this is a statistical illusion, not proof of safety. The triangle reveals why “zero” is not evidence of success but often the absence of truth-telling.

Why This Matters

The purpose of a safety triangle is not prediction – it is mobilization. Bird’s Triangle worked because it was simple and powerful, not because it was valid. The challenge is to design an equally compelling image that is not just powerful, but also truthful.

The new triangle does this in three important ways:

- It Shifts Focus from Events to Conditions

Instead of counting incidents, it directs attention to the cultural and systemic foundations of safety. What really drives accidents are not ratios of injuries, but conditions of dysfunction. - It Explains the Illusion of Zero

Organizations can have thousands of risk exposures and still report no accidents. This does not mean they are safe – it means they are lucky, or their reporting culture is broken. The triangle helps explain this dangerous illusion. - It Provides a Framework for Action

Each layer of the triangle points to interventions: strengthen culture, repair systems, support adaptive behaviors, expose risks. The path to resilience is not through counting cuts and bruises, but through addressing root causes.

Lessons from Bird’s Legacy

The Bird Triangle was wrong, but it proved something crucial: images mobilize. They can galvanize leaders, inspire commitment, and embed safety into conversations.

The task before us is to create an image with the same mobilizing power – but built on truth, not illusion. The “Pitzer Triangle” J is one attempt. It may not be perfect, but it captures the messy reality of how organizations drift into failure.

A Call to the Safety Community

The challenge we put forward is this: what image today can unite us and drive action?

If Bird’s flawed ratios could mobilize leaders for decades, surely we can design a more powerful and accurate tool for the future. The new triangle may be one such model.

Because safety is not about numbers. It is about conditions. And the right image can make that truth impossible to ignore.

This month’s article, “Rethinking the Safety Triangle: From Heinrich and Bird to a New Era, “ comes to us from Corrie Pitzer, CEO of Safemap International. Safemap is a world-recognized leader in safety and risk consulting, and we’re excited to share Corrie’s perspective with our readers. Discover more about Safemap at https://www.safemap.com/en/.

Blog Posts

Latest Posts

Related Posts